The editorial director for Outside Run became a guinea pig for a crowd-sourced run training plan. It went better—then worse—than he expected. Lessons were learned.

Foster questioning his life choices during the 2025 Bulldog Ultra 25K. (Photo: Orlando Baez)

Published September 30, 2025 03:19PM

I love crazy training plans. It probably has something to do with existing in the team environment of high school and college running in the late ‘90s and early ‘00s, where there wasn’t a lot of opportunity for individualization. Years later, call it a simple case of a midlife crisis “what-if” moment, but I figured it was time to try something new to help me rediscover my joy of running at 42 years old—something that might border on the intensity of those glory days of team running but with an extra dose of crazy..

But of course I’m no longer 21, but now exactly double that, and I don’t enjoy the luxurious, nearly monastic lifestyle of the student athlete anymore. I have a job; I have a family; I have chickens.

So what’s a 21st Century Man do when he doesn’t want to do the work but still get the results (in way less time)? The most 21st Century Man thing he can do: search the internet.

And it was here, in the depths of a very 21st Century Man running message board, that I learned about “The Norwegian Singles Training Method.”

No, this has nothing to do with dating Nordic women (or men)—despite what my Google search results now believe. It’s all of the Norwegian Training Method (no singles) without the lactate blood testing.

See, the true Norwegian Training Method (caps mine) is a hyper-specific style of training has not only led to a pile of international track medals and run records for Norway’s Jakob Ingebrigtsen, but it’s also helped countrymen Kristian Blummenfelt, Gustav Iden, and now Casper Stornes take in a haul of triathlon accolades across a previously unthinkable array of distances in a very short timeframe.

But upon digging into the Norwegian Training Method, I learned that you need to work out a ton, make nearly ritualistic use of blood lactate testing, and treat your recovery with that level of monastic reverence that I already mentioned waved bye-bye to me probably a decade or more ago (if I ever really had it). Also, I hate needles and blood and focused training.

The Norwegian Singles Training Method also has roughly half the training (hence “singles” versus the original method’s use of double-threshold days).

I was sold.

The Basics

Here, I won’t dive too deeply into the history or the methodology of Norwegian Singles—except to credit to a Letsrun.com message board poster known as Sirpoc84 who codified (and used) the style of training, where it’s laid out in a sprawling 350-plus (and counting) page thread, a public Google Doc, and Outside Run’s own independently coach-led explanation/evaluation. (Depending on the amount of free time you have, I recommend checking out at least one of those sources for more information.)

But the TL;DR is: This method builds to two to three threshold runs per week—with very easy runs in between—and a long run. It seems surprisingly simple, and maybe even “easy” in its simplicity, but my own tests told a weirdly different story, in an unexpected way. Here’s how it went for me:

The Norwegian Singles Run Training Plan Guinea Pig: The Early Weeks

Like I mentioned before, I ran in college and then later spent years as a pro triathlete, so it’s worth putting up top that I’m pretty “fluent” in running, racing, and hard training. I’m no stranger to a demanding structured run program, my biomechanics are pretty good, and my aerobic engine is far from rusty when I first cranked this thing up.

Leading into this program, I’d been running pretty consistently about three times per week, but never super hard nor super long—probably averaging less than 10 miles per day, close to 20 miles per week. Most of my runs were either “meandering” or “rushed,” as time allowed, but on incredibly hilly off-road terrain. So, to put this thing to the test, I picked a 25K trail race with tons of elevation gain (in the first hour of racing) that I’d run back in 2021.

As such, I plotted out a total of eight weeks of Norwegian singles, beginning with our own four-week sample plan, then tapped the author of Outside Run’s Norwegian Singles story, Matt Fitzgerald, to fill out the final four. As a sort of “handicap,” I didn’t have Fitzgerald hands-on coach me through the plan, and as such I didn’t go through his typical intake process to set paces—I wanted to do as much as I could on my own.

I set out on week one with this schedule:

* It’s important to note that the run paces in my plan are all “effort pace”—another term for grade-adjusted pace or GAP that adjusts for the steepness of the terrain—because I live in a very very hilly area, and short of running on a track or a mind-numbingly short stretch of flat road, there was no way pace would be accurate. I also didn’t want to do flat-only training for this trail race, given it has so much elevation gain. In hindsight, Fitzgerald strongly recommends a more controlled environment—flat road, a track, or even a treadmill—as the Norwegian method is all about control.

The first week was…interesting. My first threshold run on Monday was easier than I thought it would be, until I realized how obscenely short the rest interval is (and would always be). As someone who has used the more classic “rest half the work” formula for years, resting for only one minute after a 10-minute interval felt like just enough time to slow down before starting back up again. My heart rate had only a tiny opportunity to dip back down, and it felt more like a slight mental reset than a full physical one (which is the point).

By Friday, I had realized that the psychological challenge of running a threshold workout every other day (especially with very tight rest intervals) was going to be tougher than I thought it would be, and yet I wasn’t as fatigued as I thought I’d be for each session.

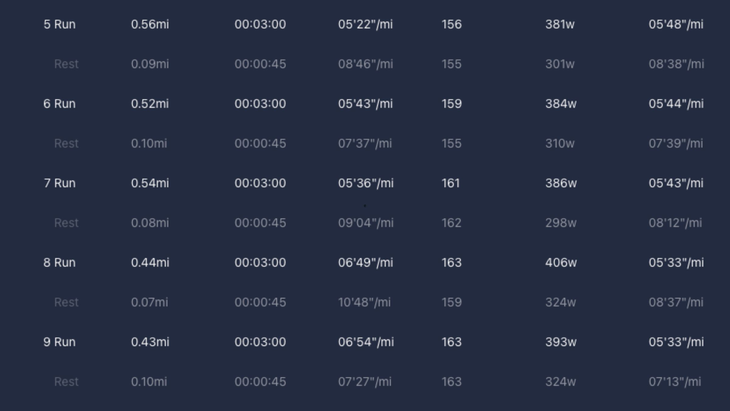

I was very, very tired on the easy days, but I magically came back to life usually midway through the first or second repeat on the threshold days. Through the first two weeks, the three-minute threshold sessions were by far the hardest for me.

The Glorious Middle

Beginning in week three and staying steady until week six (of eight), I was in the sweet spot. My heart rate stayed incredibly steady on those previously tough three-minute threshold days, and more notably, I was able to kind of “check out” during the threshold intervals.. I was able to relax a bit, even at a somewhat demanding pace and heart rate. Running hard and fast felt more natural and effortless—something that usually comes after six weeks of training, or more.

It’s also no coincidence that at the end of three weeks, I’d already done nine intense workouts—a tally that you’d usually reach closer to four or five weeks of training in a more traditional program. And yet the fatigue wasn’t compounding in a way I’d expect by effectively “squeezing in” that many workouts into that short of time.

But this is also where things started to unravel (without me knowing it), but we’ll get to that soon.

At week four, feeling so good, I decided to lower all of my LT effort paces by 10 seconds per mile, to get closer to the goal pace I was hoping to hit on race day. While my heart rate averaged a little high, immediately following that adjustment, mentally and leg-wise, I felt great.

But it’s also worth noting that I went off-script here without any guidance from the coach who had prescribed the plan to me. In hindsight, Fitzgerald himself notes that most, if not all, of my threshold paces were probably too high initially, and that by lowering them even further, I didn’t do myself any favors—to put it mildly.

“The effectiveness of Norwegian-style interval workouts is deeply dependent on knowing your exact threshold pace, power, lactate, or heart rate and using this known value to guide your effort in real time throughout every workout,” Fitzgerald explained to me after I had completed the training and racing. “For an athlete at your fitness level, LT is sustainable for about 50 minutes straight with no breaks. The fact that the breaks you got seemed inadequate even after running a small fraction of 50 minutes tells me you were doing most of your intervals above threshold and therefore weren’t really doing Norwegian-style training at all.”

However, in week five, my average heart rate dropped even more, leading me to think I had adapted to the faster threshold pace—even with more reps (11) at my least-favorite three-minute threshold. But Fitzgerald explains (in hindsight) that this was actually a signal that my nervous system was overtaxed and my body was trying to slow me down. I now understand that the Norwegian training method does not fight fair.

During my perceived “golden sweet spot time,” the 10-minute sessions felt barely even like thresholds, and the 90-second thresholds felt more like extended strides, even when upping the reps to 15, while still keeping the rest short and the pace very fast.

The Cracks Begin to Show

In week six, we added short hill sprints to the end of the long threshold session on Mondays and increased the long runs pretty substantially—from 1:25 to 2 hours. And while none of these felt harder on their own, it’s likely that the cumulative fatigue began to catch up. More than that, I had one day in particular where I didn’t “respect the rest.”

At the end of week six, rather than rest after my Saturday long run (like a good running monk), I spent almost the entire weekend on my feet, working in the yard in the sun (like an actual monk). The next week also happened to be a bit of a heat wave, which made the threshold sessions more of a struggle than they’d been during virtually the entire span of the training plan.

Day by day, it took longer to feel good during the threshold workouts, while the easy runs felt like an absolute grind.

Near the middle of week seven, I was fighting some hamstring pain that was likely triggered by lower-back/sciatica tightness. It’s not an issue that’s bothered me much in the past, but most likely because I’d simply stop running for a while, and then stretch, roll, and release. But with the nonstop back-to-back grind of the Norwegian Singles plan, which had me up to 50-55 miles/week at this point, everything became very amplified very quickly.

Near the end of week seven, I had to miss some runs with hopes of resting my back/hamstring, but it was also pretty clear that something deeper was off. I hadn’t been sleeping well for a while, and I was often sweating through the night. The fact that I was still running OK (until week seven) masked the fact that I had been digging a hole for a while.

In his own post-mortem, Fitzgerald says that the cracks had actually started to show much much earlier than even I understood—likely due to my overambitious pacing choices from day one and my poor choice of training environment on the trails.

“I probably would have recommended that you do at least some of the sessions on a track or treadmill and modified those you intended to do on the trails, as Norwegian-style interval workouts are all about precise control, which is next to impossible on hilly, technical trails,” Fitzgerald explains.

This is the End

With a few days until the 25K, I was actually feeling good, in terms of hamstring/back pain, but I was decidedly fatigued. Again, I chalked this up to the taper-week doldrums, but I also wasn’t in “LET’S CRUSH THIS THING” mode either.

What I did have was the perfect race shoes— Hoka Tecton X 3s—specifically chosen for me by our resident shoe guru, Jonathan Beverly. And I knew I had the finest run nerd crowdsourced training plan that money couldn’t even buy.

As the gun went off on a very cool, foggy Southern California morning in the Santa Monica Mountains, I quickly settled into the (fast) lead group. The guys were younger (five-plus years) and looked sharp. Within 3 miles of the 6-mile climb, I realized the lead group of four was not for me.

After about 10 minutes of feeling sorry for myself, followed by a dose of panic (“I need to stop, something is wrong with me, I need to get a blood test, like today.”), I felt a strange sense of calm: I was in the mountains, still moving relatively fast, faster than 99 percent of the population could; I could just enjoy this.

Would I be beating 2021 Chris? Zero chance.

But the Chris at the 2025 Bulldog Ultra was different in another way: I was able to adjust my mindset, midrace, to go from “think about all of the hours you spent killing yourself with this crazy training plan and this is the result?” to “I’m going to enjoy some time out here.”

I don’t think I’ve actually ever done a race in my entire life where the outcome didn’t matter and the time on the race course was time to look around.. I know that’s sad, but it’s true.

I finished that race in fourth place, which is still very, very good. I was 20 full minutes slower than I was when I was 38, and the conditions in 2025 were way better than in 2021.

But I actually had more fun than I did four years prior, and all it took was zeroing out all of the excuses for why I should or could have been faster than I actually was.

There was nothing more I could have really done—except maybe been a little more conservative/thoughtful during the final weeks of the plan, but that also wasn’t the point of this whole exercise. I wanted to go all in, consequences be damned, and see exactly where the wheels fell off if I committed fully.

So yes, I think I found that crux, but I also found that I didn’t really like training super hard. Even in that sweet-spot phase, I was having like 4/10 fun—it was better than horrible, but not as good as great. I also didn’t really like the single-minded, monastic pursuit of race-day excellence anymore.

The Norwegian Singles Run Training Plan Guinea Pig: What Was the Point?

For some, the Norwegian Singles plan might be a (very challenging) ticket to a new PR, but it wasn’t for me. It does demand a strict level of attention and respect—probably more than I could give it. It required incredibly constant/detailed monitoring, which I am admittedly terrible at. It also requires a controlled environment—like running on a track or treadmill, two things I personally hate so much that I might as well not be running at all.

The best analogy I can think of is the Norwegian Singles plan is it’s like an exotic pet: Yes, it’s really cool, and it’s fun to show off the results if you really nail its care, but exotic pet ownership isn’t for everyone—it’s costly and tricky and sometimes fraught with dangerous pitfalls. It doesn’t take much for things to go way off the rails, which can end in a pretty spectacular, public fail.

I think of the story of the family who really really wanted to raise an octopus, but then the sweet little octopus burst into over 400, which of course is very different than caring for just one (I guess).

Without spoiling the octopus story, it didn’t go great, and because it was such a big swing, it ended up being a very costly (and public) miss; but the family ended up learning a greater truth about pet ownership, in the same way that I learned a greater truth about running into middle age.

The Norwegian Singles plan wasn’t going to turn back the clock to a younger, faster me, no matter how (incredibly) hard or novel it was. For this 21st Century Man, my true shortcut to a deeper joy of running was actually, and finally, letting the racer go.